| Download PDF (Available Soon) | |

| Author and Article Information |

Abstract

Altered mental status (AMS) is a common emergency call at universities, and for collegiate-based EMS (CBEMS) providers this chief complaint is frequently found secondary to alcohol intoxication. Although it is important to consider alcohol when determining the etiology of AMS patients, a presumptive diagnosis of intoxication without a thorough differential diagnosis can delay or prevent treatment of life threats. The purpose of this study is to determine if EMTs prematurely diagnose alcohol intoxication as the etiology of AMS due to underutilization of key AMS assessments.This study was conducted as a retrospective analysis of de-identified patient care reports (PCRs) submitted between 2015-2022 from one system. PCRs were compared to predetermined criteria for AMS and examined for evidence of alcohol consumption and key assessments for AMS differential diagnosis. Assessments for AMS differential diagnoses were underutilized on all AMS calls, regardless of documentation of alcohol consumption. Moreover, EMTs completed significantly less of the expected vital signs, measurements, and assessments outlined in literature and the protocol for AMS patients when alcohol consumption was reported compared to when it was not (p < 0.05). These results demonstrate evidence that EMTs may presumptively attribute alcohol intoxication as the etiology of AMS, as evidenced by the underutilization of key AMS assessments.

Introduction

Altered mental status (AMS) is a common emergency call on college campuses, and for non-elderly patients, this chief complaint is frequently found secondary to alcohol intoxication.1

AMS refers to an assortment of clinical symptoms rather than a specific diagnosis, including impaired cognition, attention, awareness, and level of consciousness.2 Although AMS is a common emergency call, the exact etiology of many AMS patients is unknown or difficult to discern because these patients often present with vague symptoms that may be the primary presentation for a variety of medical conditions and consumption of substances.1 Alcohol and mind-altering substances should be considered when determining the etiology of AMS patients, but the presumption of alcohol intoxication as the cause without a thorough differential diagnosis to rule out alternatives is a dangerous medical decision that can delay or prevent vital treatments of life threats.3

Collegiate-based Emergency Medical Services (CBEMS) are emergency medical service (EMS) organizations located within colleges or universities that respond to on-campus emergencies to help create a healthy and safe environment. CBEMS organizations significantly differ from traditional EMS agencies because they are situated on college and university campuses, which involve complex physical layouts, frequent mass gathering events, and highly populated, confined areas. Although college campuses are composed of predominantly healthy young adults, undergraduate students have higher rates of alcohol and recreational and prescription drug misuse and are more likely to participate in binge drinking activities.4

The prehospital management of a patient with AMS should focus on basic life support measures, including assessing the patient’s ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation), checking vital signs, and addressing any life threats.5 There are five generally recognized vital signs, pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature, and blood oxygenation (SpO2). Once the ABCs and life threats are adequately addressed, EMTs should use the exam, history, vital signs, and additional evaluations to develop a broad differential diagnosis and identify a possible specific cause or causes of AMS that could benefit from specific treatment or transport by ALS.5 A differential diagnosis is a systematic process used by healthcare providers to identify a proper diagnosis from other possible competing diagnoses, which involves distinguishing a possible condition as a possible cause of the patient’s illness or abnormal presentation via process of elimination.6 The common causes of AMS are illustrated by the mnemonic AEIOU-TIPS shown in the box below.

Figure 1: Mnemonic for common causes of AMS 5, 7

| A – Alcohol E – Epilepsy, Electrolytes I – Insulin (hypo-/hyperglycemia) O – Oxygen, Overdose U – Uremia T – Trauma, Temperature I – Infection P – Poison, Psychiatric S – Stroke, Shock, Sepsis |

Alcohol is only one of 14 categories for possible causes of AMS outlined by the mnemonic AEIOU-TIPS. Additional evaluations and measurements conducted by EMTs can be used to assess if the patient’s AMS can be attributed to or to rule out a common cause of AMS; therefore, helping to narrow down the possible conditions leading to the change in the patient’s mental status by process of elimination. For example, a blood glucose measurement can help EMTs identify if an insulin-related condition is affecting the patient’s mental status.5, 7 To give another example, abnormal pupils may indicate trauma, overdosing, or poisoning.5, 7 In the context of this study, AMS assessments do not refer to an evaluation of the patient’s mental status, but instead refer to measurements, such as vital signs and additional evaluations that should be conducted by EMTs to determine the possible cause or causes of AMS. The assessments chosen for this study are specifically outlined the expected protocol for AMS patients written by the medical director of this CBEMS organization. These assessments include blood glucose measurement, SpO2, test of pupil reaction and size, evaluation of possible head trauma, temperature, and Cincinnati stroke evaluation.8 The literature also describes these assessments as crucial in the prehospital management of AMS patients.5, 7, 9

The purpose of this study is to analyze the evaluation of AMS patients by emergency medical technicians (EMTs) from a CBEMS organization to determine if there is a significant difference in whether or not EMTs follow the expected protocol to rule out possible causes of AMS for patients when they report alcohol consumption compared to when alcohol is not reported. Due to the high rates of alcohol use and binge-drinking on college campuses, we hypothesized that EMTs may not conduct all necessary measurements and evaluations outlined in the protocol for AMS patients when alcohol is involved. There is a lack of literature on the treatment of altered mental status patients by EMTs from CBEMS organizations in general and regarding the relationship between this chief complaint and the consumption of alcohol. This is the first study to examine the association between the consumption of alcohol and the frequency at which the six AMS assessments of interest for this study are completed during altered mental status calls.

Methods

The study was performed at a private college with a student population of around 3,000 undergraduate students. The CBEMS organization from this study is a student-run, volunteer organization of EMTs that provides basic life support (BLS) non-transport emergency medical services on weekdays from 1900-0700 and 24 hours on weekends during the academic year. For advanced life support (ALS)-level acuity calls and calls requiring transport, an ALS-level transport ambulance can be dispatched. Campus Public Safety is also able to transport low-acuity patients to the local emergency department without charge if the patient requests after they have been released.

This was conducted as a retrospective chart review and analysis of patient care reports (PCRs) between September 2015 and June 2022. A total of 791 PCRs were submitted by EMTs during this time period using a password protected form on a college-sponsored Pages website. De-identified data from these call records were extracted from the Pages website using the “Export Entries” function. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board; informed consent was waived because the data for this study was gathered as de-identified records stored on a secure, password-protected database.

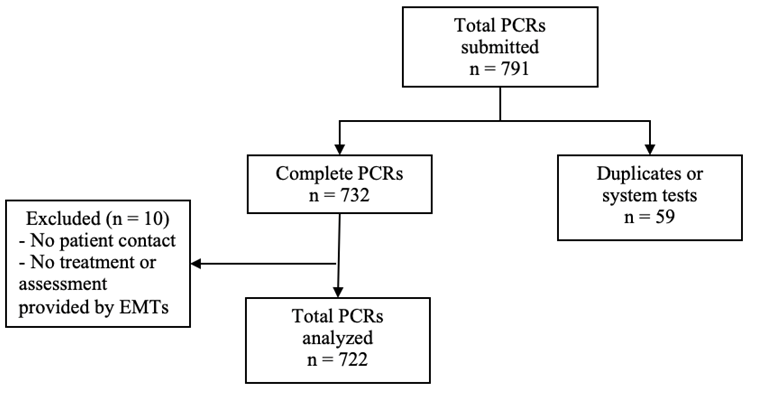

Of the 791 PCRs submitted between September 2015 and June 2022, 732 were identified as complete PCRs and 59 were identified as duplicates or system tests. Duplicates and system tests were excluded from this analysis. Out of the 732 complete call records, 10 further PCRs were excluded from the data set due to the lack of patient contact or lack of treatment/assessment provided by EMTs. These 10 PCRs refer to instances in which EMTs arrived on scene after the ALS ambulance and observed the ALS providers without providing any care to the patient themselves. This resulted in a total of 722 PCRs analyzed for this study over the seven academic year study period.

Figure 2: Flow diagram of included patient care reports (PCRs)

In this study, we sought to identify all patients who presented to EMTs with an altered mental status, including patients in which AMS was not recorded as their chief complaint or reason for calling. Each complete PCR used in this analysis was reviewed and calls were characterized as altered mental status or non-altered mental status based on predetermined inclusion criteria of altered mental status developed by reviewing the literature definition and EMS protocol from the medical director.

Inclusion Criteria:1, 5, 8, 9

- A&Ox4 < 4 at any point

- GCS < 15 at any point

- Change in baseline mental status

- Abnormal/bizarre behavior

- Decreased mental status/lethargy

- Impaired decision-making capacity

- Altered level of consciousness (ALOC) at any point

- Slurred and/or slowed speech

A&Ox4: alert & oriented to 4 points (person, place, time, and situation); GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale

After the identification of all AMS calls using the inclusion criteria, each PCR was reviewed for the following assessments that are outlined in the protocol by the medical director for this CBEMS organization and are supported by literature on the prehospital management of AMS patients. If performed correctly, these assessments are key to the differential diagnosis of the AMS patient to help discern the etiology of their change in mental status. Each PCR was also examined for a report of alcohol consumption by the patient. For a PCR to be categorized into the alcohol (EtOH) group, it had to be clearly documented in the call record. If it was unclear whether or not the patient ingested alcohol, the PCR is categorized in the no EtOH group.

AMS Assessments:

- Blood glucose

- Pupils

- SpO2

- Head trauma assessment

- Temperature

- Cincinnati Stroke Scale

The PCRs were examined for the presence of each AMS assessment identified above. For an assessment to be considered completed, it must be clearly stated in the run report that EMTs either completed this assessment or attempted to complete it. There were several calls in which the EMT was unable to complete the assessment due to a machine error or combative patient behavior. These call records were marked as a completed assessment because it demonstrates that the EMT considered other causes for AMS beyond alcohol consumption. Assessing a patient for head trauma in the context of this study refers asking the patient/bystander, visual inspection, or palpating the head. For calls in which no head trauma assessment was counted for this study, this means that none of these evaluations were documented in the PCR.

Pearson χ2 tests for independence (categorical variables) and a Welch two sample t-test (continuous variables) were used to examine the relationship between alcohol consumption in AMS calls and the frequency at which the identified assessments were completed. If the expected values were less than 5 for a Pearson chi-square test of independence, Fisher’s Exact Test was used instead.10 Significance level was set at p < 0.05. Bayesian statistics were used to account for the base rates of the varying assessments used during different call types. The data was analyzed using RStudio.

Results

Over the seven academic year study period, we identified 207 PCRs out of 722 that met the inclusion criteria for AMS to be analyzed in this study. This number of PCRs represents approximately 29% of patient volumes from 09/2015-06/2022. Alcohol consumption was documented in a majority of AMS identified PCRs (161, 77.8%).Of the 161 AMS calls in which alcohol consumption was reported, 48 (29.8%) were released to self, 5 (3.1%) were transported by campus public safety, 107 (66.5%) were treated and transported by ALS, and 1 (0.62%) refused treatment. Comparatively, of the 46 AMS calls in which alcohol consumption was not reported, 11 (23.9%) were released to self, 10 (21.7%) were transported by campus public safety, 24 (52.2%) were treated and transported by ALS, and 1 (2.2%) refused treatment.

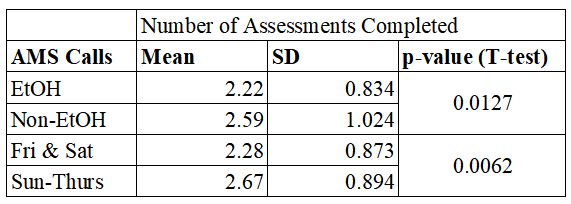

Table 1 summarizes the mean and standard deviation of the number of AMS assessments completed for AMS calls between those when alcohol (EtOH) was reported and when alcohol was not documented. The average number of AMS assessments completed was significantly higher during calls when alcohol was not reported (mean = 2.59, SD = 1.024) than for calls in which alcohol consumption was documented (mean = 2.22, SD = 0.834) (P-value = 0.0283).

Table 1: Comparison of the average number of identified AMS assessments using T-test

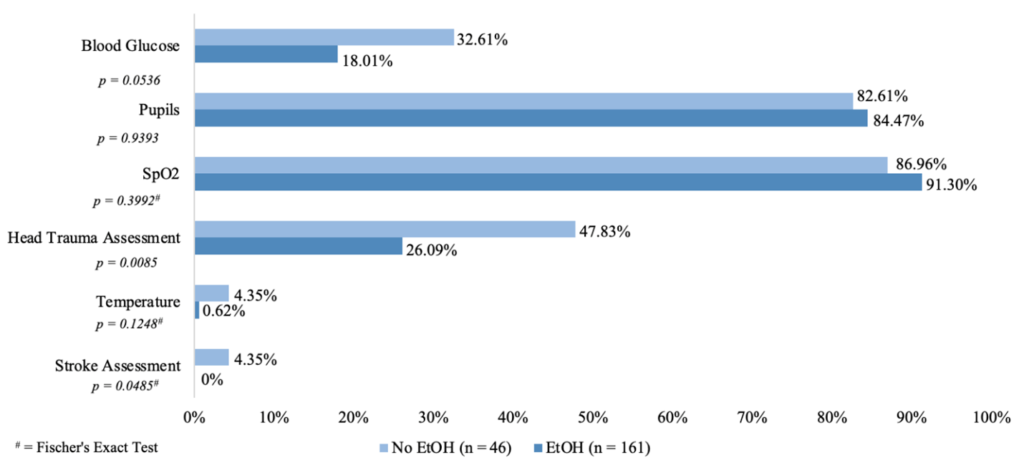

Figure 3 compares the frequency at which AMS assessments were completed between alcohol-related and non-alcohol related AMS calls. Results from the χ2 tests and Fisher exact tests showed significant differences in the frequency at which AMS patients were evaluated for head trauma and the rate at which a stroke assessment was completed (P-value = 0.0085, P-value = 0.0485). There was no significant difference in the frequency at which blood glucose, pupils, SpO2, and temperature were taken. There was no significant difference observed for temperature and a significant difference observed for stroke assessment; however, the incidences of these assessments are too low to interpret as being done more during one call type.

Figure 3: Comparison of the frequency of AMS assessments between AMS calls with and without alcohol (EtOH)

The conditional Bayesian probability of EMTs performing a head trauma assessment given that alcohol consumption was reported is 0.2608 compared to 0.4787 when it was not reported.

Discussion

This study provides the first published evidence of the relationship between the consumption of alcohol and the number of assessments completed by collegiate EMS providers. During the study period, AMS calls were the most common call type responded to by EMTs, comprising 29% of the total call volume over the 7 academic year study period. Alcohol consumption was documented in a majority of AMS calls.

This study shows that whether a patient reported consuming alcohol is correlated with a decrease the number of vital signs and assessments completed by EMTs in this dataset. During AMS calls in which alcohol consumption was reported, EMTs, on average, completed significantly fewer assessments compared to calls in which alcohol was not documented. Additionally, EMTs assessed for head trauma significantly less for AMS patients who reported alcohol consumption. This is especially concerning as patients who have consumed alcohol are at an increased risk for severe head trauma.11, 12 Although the p-value for blood glucose is slightly greater than 0.05 (P-value = 0.0536), indicating no significant difference, the rate at which this measurement was taken is lower than 50% for both groups. The failure to collect a blood glucose measurement on any AMS patient is worrisome as it is considered a universal step in the management of AMS patients and can indicate an easily reversible cause of the patient’s change in mental status.2, 5The incidences of EMTs taking a temperature and performing a stroke assessment were nearly 0 in all groups, indicating an overall absence of these assessments in the differential diagnoses performed by EMTs for AMS patients. Strokes are rare in college-aged adults, with only 10-15% of strokes occurring in individuals under the age of 45.13 Therefore, it is not surprising that this step was often neglected in the differential diagnosis of AMS patients by EMTs on a college campus. However, the absence of completing a stroke assessment is still a deviation from the expected protocol for AMS patients.

When examining the dispositions of AMS patients, we determined that a greater percentage of patients who reported alcohol consumption were released to self compared to those who did not report this consumption. Likewise, we found a greater percentage of treatment and transport by ALS for AMS patients that reported consuming alcohol. Conversely, a smaller percentage of AMS patients who consumed alcohol were transported by campus public safety. Based on these results, it is difficult to determine if patient disposition (released to self/campus public safety vs. ALS – higher level of care) is correlated with a change in the thoroughness of the differential diagnosis conducted by EMTs.

We also identified an underutilization of key assessments in all AMS calls. On average, less than 3 out of 6 recommended assessments were completed, whether or not the patient reported alcohol consumption during all EMT shifts. Our results demonstrate a general gap in the care of AMS patients by EMTs on this college campus and a lack of adherence to protocol when treating and evaluating patients with a change in mental status. Ultimately, these results provide evidence that EMTs do not complete adequate differential diagnoses for AMS patients when they report the consumption of alcohol. Due to the nature of EMS, specifically the inability to definitively diagnose patients, there is no way to know for certain if a patient’s change in mental status can be attributed to any one cause of AMS. Therefore, this prevents us from determining if alcohol is simply the most common cause of AMS among patients in this study or if alternative causes are truly being missed. However, the results indicate a correlation between inadequate differential diagnoses and alcohol consumption, suggesting that EMTs may be presuming alcohol intoxication as the etiology of the patient’s change in mental status since they are not completing additional assessments to rule out other potential causes.

For appropriate prehospital management of AMS patients, a broad differential diagnosis should be considered and maintained through ongoing evaluation of the patient’s condition and determining if the patient presents with any conditions that can be treated on scene or if the patient requires an additional level of care. Rapid treatment is required for some causes of altered mental status and by not conducting the appropriate vital signs, measurements, and additional evaluations, EMTs may not be able to accurately determine the appropriate treatment and safest disposition for their patient. Since the results of our study show an underutilization of the key assessments and a failure to follow protocol for AMS patients regardless of the reported consumption of alcohol, it is possible that some patients were not given proper care for their condition(s).

The specific significance of a presumptive diagnosis of alcohol intoxication is illustrated in a study by Martel et al., who suggests that based on the frequency of alcohol intoxication as the etiology of AMS, some providers may decide not to pursue additional testing or diagnostics when patients present to the emergency department (ED) with a report of alcohol consumption or intoxication.3 It was found that 5% of these patients were assumed to be intoxicated based on their primary history, but actually had a different clinically significant cause for their AMS, including illicit substances, trauma, medical causes, and psychiatric etiologies.3 Of these missed patients, 10% required hospitalization and nearly 2% required ICU level of care.3 Although Martel et al. highlights the concern with presumptively diagnosing patients with alcohol consumption, their sample only included patients who were identified to have an undetectable breath alcohol concentration, meaning there may be additional patients who presented with confirmed alcohol intoxication, yet were also found to have an additional condition contributing to their AMS. We found that when patients reported the consumption of alcohol, EMTs did not complete a thorough differential diagnosis to rule in or out additional conditions affecting the patient’s mental status, thereby potentially preventing necessary treatment to reverse or aid these conditions.

Existing literature on acute alcohol use in prehospital young adult patients suggests that patients who consumed alcohol are more likely to present with head and neck injuries, compared to those who did not consume alcohol.11 Additionally, alcohol consumers were found to be more likely to require spinal immobilization and have ALS activated.11 The results from our study demonstrate that the EMTs did not evaluate all AMS patients for possible head trauma and, in fact, assessed less AMS patients for head trauma when alcohol was reported. Therefore, by not evaluating all AMS patients for possible head trauma, especially those who report the consumption of alcohol, EMTs could not correctly determine if their patient required these interventions, potentially leading the EMTs to miss an injury to the head or neck. Without the identification of an injury to the patient’s head or neck, EMTs may not have provided sufficient treatment of the patient’s conditions.

Limitations

This study should be examined within the context of several limitations. Since this study was completed as a retrospective review of EMT PCRs, it is possible that the AMS inclusion criteria could have missed some eligible PCRs to be classified as AMS. Furthermore, the classification of AMS, in of itself, is somewhat subjective because patients present with a variety of vague symptoms. The PCR form does not specifically require the documentation of a patient’s mental status (i.e. GCS, Awake Verbal Pain Unresponsive – AVPU, or A&O), nor is this always included in the written narrative. As this study relied on previously collected data, there was no way to measure the reliability of EMT ratings of a patient’s mental status using AVPU, GCS, and A&O. Therefore, it is probable that there were some cases classified as non-AMS when the patient did present with AMS.

The narrative structure of PCRs and the lack of a specific documentation requirement of a patient’s mental status makes it possible for subjective interpretation to exist between observers. For this study, one reviewer classified calls based on the inclusion criteria for AMS. As such, a bias may exist, and our PCR classification could have benefitted from an additional reviewer and statistical analysis on inter-rater reliability.

The PCR form also does not specifically require the documentation of alcohol consumption. If alcohol consumption was not reported in the narrative or any other area within the submitted PCR, it was classified as non-alcohol related. Additionally, the college at which this research was conducted has a dry campus policy and although there is a medical exemption for students receiving care while under the influence of substances, this can lead students to choose not to disclose their consumption of alcohol for fear of disciplinary action and violations added to their permanent academic record. Consequently, there are likely several cases in which a patient did not disclose their consumption of alcohol to EMTs, resulting in an underestimation of calls involving alcohol.

Unlike the documentation of alcohol consumption and a patient’s mental status, the EMT PCR form does specifically require the documentation of a patient’s pupillary response if it was taken. Although the PCR form requires documentation of pupillary response, the default within the form was set as “Normal – PERRL” rather than “Not Obtained”. Therefore, it is probable that the frequency at which pupils were taken is overestimated for all calls.

The data used for this study was de-identified both for patient name and the names of EMTs responding to the call. This means it is unknown whether a call is for a new patient or the same patient with a worsening condition. Furthermore, without the names of the EMTs, we cannot determine whether there were trends in the care provided to AMS patients by specific EMTs.

The 7 academic year study period encompasses the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, students were sent home for the rest of the semester and the following fall, students were provided with the opportunity to stay home and attend their classes online. This decreased the student population on campus. Heavier penalties were also enforced for the consumption of alcohol and on-campus parties to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Less on-campus events occurred, such as dances, sporting events, and performances, which typically were staffed by EMTs. Traditionally, students are on-campus for the month of January to take a J-term class; however, these courses were moved online for 2021 and 2022. This all likely contributes to a lower call volume and reduction in the number of calls available for statistical analysis for this study.

Lastly, the setting in which this study was conducted is relatively unique as a CBEMS organization located on a small liberal arts college. This study would have to be replicated at other universities and traditional EMS organizations to test whether these results are generalizable.

Conclusion

Of the six AMS assessments of interest in this study, on average, significantly less of these assessments were completed by EMTs for AMS patients who reported alcohol consumption and for AMS patients who called for EMTs during a Friday or Saturday shift. Moreover, the rate of assessing an AMS patient for head trauma was significantly lower in AMS patients reporting the consumption of alcohol. When treating patients with AMS, EMTs should maintain awareness of possible bias towards attributing the change in mental status to alcohol and, consequently, not completing a thorough differential diagnosis by conducting all necessary vital signs, measurements, and evaluations to rule in or out potential causes for AMS.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Lynn and Mary Steen Foundation at St. Olaf College for supporting and funding this project. The author would also like to thank Kathryn Ahnger-Pier and Dr. Kevin Crisp for their mentorship and guidance throughout this project. Lastly, the author would like to acknowledge and thank the St. Olaf EMTs for their continued support for this project and their important work keeping the students on St. Olaf’s campus safe.

References

- Xiao H, Wang Y, Xu T, et al. Evaluation and treatment of altered mental status patients in the emergency department: Life in the fast lane. World Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;3(4):270. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.04.006

- Clinical Policy for the Initial Approach to Patients Presenting With Altered Mental Status. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1999;33(2):251-281. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70406-3

- Martel ML, Klein LR, Lichtenheld AJ, Kerandi AM, Driver BE, Cole JB. Etiologies of altered mental status in patients with presumed ethanol intoxication. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018;36(6):1057-1059. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.03.020

- Caamaño-Isorna F, Moure-Rodríguez L, Doallo S, Corral M, Rodriguez Holguín S, Cadaveira F. Heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related injuries: An open cohort study among college students. Accid Anal Prev. 2017; 100:23-29. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2016.12.012

- Luciano-Feijoó M, Williams J. Chapter 15: Altered Mental Status. In: Emergency Medical Services: Clinical Practice and Systems Oversight. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2021:152-157.

- Kaiser C. Differential Diagnoses are Important for Patient Outcome – JEMS: EMS, Emergency Medical Services – Training, Paramedic, EMT News. Published February 29, 2016. https://www.jems.com/patient-care/differential-diagnoses-are-important-for-patient-outcome/

- Sanello A, Gausche-Hill M, Mulkerin W, et al. Altered Mental Status: Current Evidence-based Recommendations for Prehospital Care. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health. 2018;19(3). doi:10.5811/westjem.2018.1.36559

- Fischer J. Care Guidelines: Altered Mental Status. In: Northfield Hospital and Clinics EMS Patient Care Guidelines. Northfield Hospital and Clinics; 2022:1-3.

- Samuels D, Bock M, Maull K, Stoy W. EMT-Basic: National Standard Curriculum. Published online 1996. https://www.ems.gov/pdf/education/Emergency-Medical-Technician/EMT_Basic_1996.pdf

- Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics. 2017;42(2):152-155. doi:10.5395/rde.2017.42.2.152

- Barton DJ, Tift FW, Cournoyer LE, Vieth JT, Hudson KB. Acute Alcohol Use and Injury Patterns in Young Adult Prehospital Patients. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2016;20(2):206-211. doi:10.3109/10903127.2015.1076101

- Weil ZM, Corrigan JD, Karelina K. Alcohol Use Disorder and Traumatic Brain Injury. Alcohol Res. 2018;39(2):171-180.

- Smajlović D. Strokes in young adults: epidemiology and prevention. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:157-164. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S53203

Author & Article Information

Margaret Dickey, EMT-B is the current Quality Improvement Officer for the St. Olaf Emergency Medical Technicians (SOEMTs) organization and a senior at St. Olaf College. Kevin Crisp, PhD, EMT-B is a Professor of Biology, the Chair of the Health Professions Committee, and the Faculty Advisor for the St. Olaf Emergency Medical Technicians (SOEMTs) organization at St. Olaf College.

Author Affiliations: From St. Olaf Emergency Medical Technicians at St. Olaf College – in Northfield, MN (M.D., K.C.).

Address for Correspondence: Kevin Crisp | Email: crisp@stolaf.edu | Mailing Address: 1500 St. Olaf Ave, Northfield, MN, 55057, USA.

Conflicts of Interest/Funding Sources: By the JCEMS Submission Declaration Form, all authors are required to disclose all potential conflicts of interest and funding sources. All authors disclosed their affiliation with St. Olaf Emergency Medical Technicians organization and declared no other conflicts of interest. Funding for this research was provided to Margaret Dickey from the Lynn and Mary Steen Foundation at St. Olaf College which promotes and sponsors independent undergraduate research and scholarship. No additional funding was received to conduct this research and/or associated with this work.

Authorship Criteria: By the JCEMS Submission Declaration Form, all authors are required to attest to meeting the four ICMJE.org authorship criteria: (1) Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND (2) Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND (3) Final approval of the version to be published; AND (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Submission History: Received March 8, 2023; accepted for publication October 2, 2023

Published Online: November 28, 2024

Published in Print: Pending

Reviewer Information: In accordance with JCEMS editorial policy, Original Research manuscripts undergo double-blind peer-review by at least two independent reviewers. JCEMS thanks the anonymous reviewers who contributed to the review of this work.

Copyright: © 2024 Dickey & Crisp. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The full license is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Electronic Link: Pending