Establishing a collegiate Emergency Medical Service (EMS) facilitates faster, safer, and more accessible healthcare for all members of the college community. Our EMS team at the Claremont Colleges provides first-response basic life support to our community, as well as education and assistance with licensing for new and prospective student Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs).

The Claremont Colleges are a consortium of 5 undergraduate and 2 graduate institutions. The undergraduate colleges share programs, courses, and regional location: they border each other across one square mile of land. All 5 undergraduate colleges share resources such as classrooms, dining halls, libraries, and social events. Those unfamiliar with the campus may arrive at unintended destinations as distinguishing one college from the next is difficult; this is due to the subtly defined borders between the schools. Additionally, access to buildings, classrooms, and residential halls by car is limited, catering towards pedestrian and golf cart access.

We created our service at the Claremont Colleges to meet the growing need for immediate medical assistance in our community. During medical emergencies, students were directed to call Campus Safety, who then could contact 911. The Claremont Colleges relied exclusively on third-party EMS responses prior to this program. However, the reliance on these outside services posed safety concerns as they encountered longer commute times and greater navigational difficulty on our unfamiliar campuses. Campus Safety personnel were often stationed on-scene or arrived within 2 minutes of an emergency; their presence at campus events and familiarity with the campus layout contributed to their rapid response times. In contrast, LA County Firefighters would arrive after 4 minutes and determine the need for private third-party EMS transport. If requested, private EMS would arrive after 9 minutes. We also learned that the multitude of unfamiliar responders impacted patient care. Students were less comfortable voicing their health wishes to non-consortium responders, which increased their risk and vulnerability in emergency situations. The public health benefits accompanying faster response times and collegiate-affiliated emergency services has been cited by experts in the field as well as EMS divisions at institutions such as The University of San Francisco.1,2 To address these community health concerns, an internal EMS was developed.

Accommodating the needs of our community, the Campus Safety Emergency Medical Service contributes to student wellness by employing student-EMTs. These undergraduate healthcare professionals can provide immediate care by rapidly responding to on-campus medical emergencies, professionally advocate for patients, and monitor them for symptoms of deterioration should they refuse hospital transportation.

Our service was modeled after other existing collegiate EMS programs. We partnered with UCLA, USC, LMU, Dayton, Chapman, Cal State San Bernardino, Cal State LA, Cal State Long Beach, Cal State Fullerton, and Colorado College. These schools have helped guide the assembly of a student-EMS program with their history, resources, and experience. The service was initially set to launch in the spring semester of 2020 as an extension of Campus Safety. The program was designed under the guidance of Campus Safety in order to best adapt the service to the wider community.

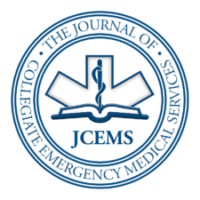

This article outlines the process of establishing a collegiate EMS (Figure 1) using our experience at the Claremont Colleges as a case study for prospective collegiate EMS agencies.

Phases

Figure 1: Flowchart detailing the sequence of steps in establishing a collegiate EMS program

Phase 1: Ensure Necessity and Interest in the Program

We discovered the community’s interest in and need for a student-employed EMS by conducting a noncomprehensive survey of the student bodies from the 7 Claremont Colleges (Appendix C). Recognizing the gap in medical care on campus, students advocated for improved emergency medical services. Students mentioned that they would benefit from adjustments to the current system. These include extended medical services (e.g. hours and staffing) in addition to Student Health Services, and supplementary resources for physical and mental-illness related medical resources on-campus.

Although the survey results presented an apparent need for a campus-based EMS agency, the Claremont Colleges Emergency Medical Systems team recognizes potential limitations in the study’s fidelity. The survey, which was distributed to the student body via Facebook and email, did not collect demographic data. Out of a total population of 8,500 undergraduate and graduate students, our survey received between 36 and 42 respondents. In the future, prospective EMS agencies should consider utilizing a numerical scale questionnaire to assess student interest for a campus-based EMS agency. Additionally, they could more effectively inform students of the survey by utilizing students’ preferred social media platforms: Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat.3 By focusing on a quantitative and mass-circulated study, other prospective collegiate EMS agencies may be able to justify establishing the agency through more empirically-based evidence.

Nonetheless, following the culmination of our survey, we learned of further student input from anecdotal data. Students recorded a preference for disclosing personal information to a peer when in crisis and would be more likely to reach out to them as opposed to a third party for financial reasons. It became apparent that students preferred to be evaluated by a peer to determine whether they needed higher levels of care (i.e. transportation to a hospital) through conversations at events the EMS club tabled at, including campus club fairs and the EMS club’s own outreach programs. Following a series of additional surveys and conversations with the student bodies, our EMS program was established to accommodate the expressed needs of our community.

After recognizing our student body’s interest for a peer-driven EMS, a team of students mobilized to both obtain EMT-B licensing and train future student-EMTs in order to ensure there would be employable students when the service began. The team began researching the feasibility of a student-EMS program on campus. This involved analyzing statistical data, protocols, and operating procedures generated by established programs. Furthermore, the process of initiating a collegiate EMS was outlined during conversations with the National Collegiate Emergency Medical Foundation and the University of Dayton’s EMS. After extensive research, the team ultimately decided to model the service after Colorado College’s EMS since our connection with them granted us access to their resources and protocols. Furthermore, the structure and student population between the two schools was similar, making it a natural fit.

Phase 2: Organization

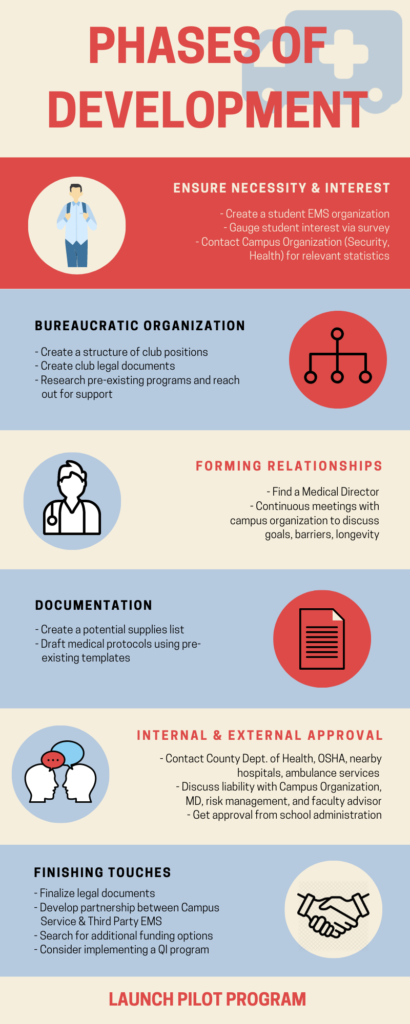

We established ourselves as a club open to all students of the Claremont Colleges to effectively organize our interested members. Creating officer positions within our club allowed us to delegate tasks for the documentation of our mission, constitution and bylaws. As an established club, we conducted research and communicated with experts in emergency medicine by reaching out to other collegiate EMS organizations. Our team then sought out a partnership with a local EMT training school. This partnership facilitated club member certifications by creating a streamlined and consistent training method for them (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Timeline of events in gaining EMT-Basic Certification. Additional steps may be required depending on location

We were faced with the decision to either initiate our service through Campus Safety or Student Health Services (SHS), both of which serve all 7 of the Claremont Colleges. Because Campus Safety was a 24-hour service that responded to emergent medical needs, whereas SHS operated during standard clinical hours, we concluded that Campus Safety should house our service.

Phase 3: Forming Relationships

Our club then began laying the groundwork to establish our EMS. Members of our club reached out to medical directors in our area, which proved to be difficult. We searched for a medical director by asking physicians from nearby Emergency Departments and connecting with others through LinkedIn. After contacting over eighty emergency medicine doctors, we found an alumnus who became our service’s medical director. Because alumni have geographical and sentimental ties to their colleges, we recommend networking with them first when searching for a medical director.

Phase 4: Documentation

After onboarding a medical director, we created a supplies list (with corresponding projected costs) and formed our medical protocols. These protocols were based on the Los Angeles County Emergency Medical Services Agency (EMSA) recommended protocols. The EMSA protocol template informed our charting layout, operating procedures, and service structure. Prior to final approval, the supplies list and protocols were reviewed by our medical director.

Other schools in the Los Angeles area aided us in drafting our protocols by providing their knowledge of local laws regarding EMS. Therefore, we recommend nascent collegiate EMS teams to contact local hospital emergency departments and nearby collegiate medical services for guidance in the development of their protocols and overall program.

Phase 5: Funding and Approval

After documenting paperwork and establishing connections for our program, our team obtained funding as well as authorizations from internal and external organizations.

On campus, we continued communicating with Campus Safety and our medical director while we began discussions with risk management. These talks revealed that insurance, liability, and funding would pose barriers to our service’s establishment. While our medical director requested full indemnity for his services, our risk management official explained that it would not be feasible for the Colleges to assume that level of risk by themselves. During these discussions, we served as an intermediary between the two parties and emphasized the importance of modeling our service after similar EMS agencies. Furthermore, we reached out to partner collegiate EMS agencies regarding model legal relationships between risk management and medical directors. With this information, our risk management team was then able to begin formulating the structure of our legal documents. Our efforts also inspired the risk management team to contact other risk managers of local schools for questions and guidance regarding collegiate EMS insurance coverage. The risk management team utilized this information to draft legal documents that provided our student-EMTs with malpractice insurance and mitigated the liability placed on our medical director.

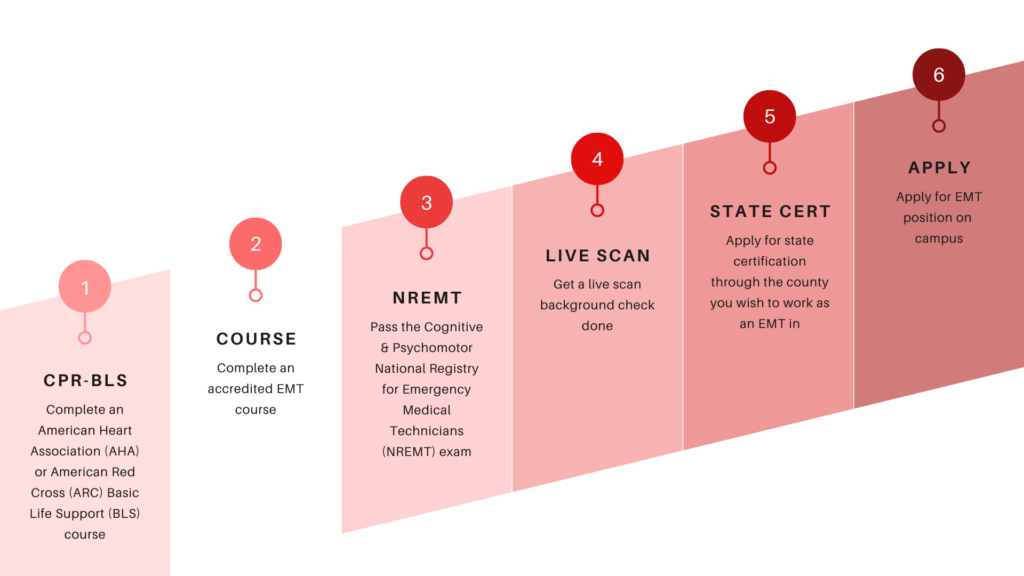

Figure 3: Geographical distribution of NCEMSF groups across the United States

During this time, we also learned that student clubs organizations may not have the funds to support such an expensive program and as such forming partnerships with established community organizations may provide essential resources for the service. We required funds for our start-up costs (e.g. radios, medical vehicle) and service costs (e.g. medical supplies). Initially, our team reached out to on-campus organizations for financial assistance and partnerships. The team first looked to form a relationship with the Keck Graduate Institute School of Medicine; they could provide a source of medical supplies for the Campus Safety EMS. As the medical school was still in its early stages of initiation, the Keck administrators mentioned that they eagerly anticipated a future partnership but would not be able to provide any financial assistance or supply exchanges until the school was established. The team also applied for funding through the Claremont Colleges clubs organization. During the presentation of our ideas and vision, we received overwhelming support for the Campus Safety EMS. However, as we required significantly more than what their budget could accommodate, we could not secure any funding. Instead, through discussions with Campus Safety, we learned that they could support our service costs but would require external financial resources to cover the start-up costs. These start-up costs were later covered by the Student Dean’s Council (comprised of the respective Dean of Students from each Claremont College) who were recommended to financially support our program by Campus Safety. From these experiences, our financial team learned that a collegiate EMS should first search for funding from entities that they are already actively working with. Even if these entities do not have the funds themselves, they may recommend additional entities to contact; they will also advocate for the collegiate EMS agency.

Another barrier we encountered was obtaining official approval for the service from the Student Dean’s Council (SDC). We had contacted the SDC on many occasions to formally present our program for their board. We understood that the formal proposal would be followed by an official vote for or against the program’s establishment. Our efforts, however, failed to gain traction as we were denied an audience with them. We then had team members from each Claremont College contact their respective Dean of Students and request individual meetings. During these discussions, our team members answered questions and clarified our program goals and vision. We believe that these meetings were instrumental to our eventual approval as they allowed the program to gain support from individual administrators before it was formally presented to them. Through these discussions, individual administrators also informed us that the SDC would be much more receptive to hearing the program’s proposal if it were presented by an established campus organization such as Campus Safety. After explaining our findings to Campus Safety, they reached out to the SDC and were able to set up a formal meeting for the program’s proposal. Campus Safety’s proposal resulted in the official approval of our program: we were established as a division within Campus Safety. Through these experiences, we learned that a collegiate EMS may benefit from contacting administrators individually and from asking a more established organization to present the program on behalf of the student group. These two actions improve administrators’ perceptions of the program before the formal proposal and legitimizes the program, making it more palatable for a college’s administrators.

Concurrently, we obtained recommendations from external organizations like Occupational Safety & Health Administration and the Los Angeles Department of Health. During this phase, we also recommend establishing connections with local hospitals and ambulance services for region specific advice and additional support.

Phase 6: Finishing Touches

Having secured the resources and established relationships on- and off-campus, we prepared to launch the pilot phase of our program. We explored different charting systems: both paper and electronic. After verifying our training procedures with Campus Safety, an application to work on the service was created. The position was available to all Claremont College students, six of which were eventually chosen to join the team. We decided that during the pilot phase, student-EMTs would work during peak hours and respond to calls in conjunction with Campus Safety. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the pilot program had to be postponed. When circumstances allow our service to launch, our goal is to expand its size by adding more certified student-EMTs who can meet our campus’ need for immediate medical attention.

Once the program begins, we have many goals to continually improve the Campus Safety EMS. We plan to gather data on the type of emergencies occurring (e.g. demographic, call location, call response time, severity), which will help us adapt our service to meet the specific needs of the population we serve. Additionally, the pilot phase serves to increase awareness about the campus service before the complete program is instituted.

As we continue to grow, we hope to implement a Quality Improvement program by hiring students from either of the Claremont graduate colleges, search for additional funding, and establish collaborative partnerships with county fire departments through student ride-alongs.

Conclusion

Throughout the process of creating our collegiate EMS, we realized that first-aid response and emergency medical training are often confined to the pre-health student community. The relatively small size of this community limits the number of individuals (i.e. first responders) that can engage in life-saving interventions during a medical emergency. Since collegiate EMS organizations should address a multifaceted student need, we believe that they should foster student education on emergency preparedness in addition to their primary concerns to guide interested students through the certification process.

As detailed in phase 2, our organization sought an EMS education partnership with a local EMT training facility. This partnership allowed our club members to gain EMT certifications at a subsidized rate as well as provide members with a streamlined process in attaining their certification. Colleges intending to start a collegiate on-campus service should consider fostering a relationship with a local EMT training facility. Such a partnership will make certification more accessible for students and therefore maximize the number of students with an EMT certification. Having a large group of students certified will not only help the service grow, but will also give traction to the service when gaining approval from administrative committees.

Colleges and universities seeking to implement a collegiate service on their campus can best benefit from this guide by extracting general steps from each phase outlined as summarized by Figure 1. They must also keep in mind that the process is not as clear cut as is shown in the separate phases. Certainly, some steps had to be completed before moving on to the following phase, such as securing a Medical Director and acquiring the proper documentation. Still, most tasks overlapped with each other nonlinearly, as very few of them could be quickly checked off a list in stepwise fashion. Furthermore, institution format and student population size should be taken into account; for example, larger schools may face more barriers and requirements throughout the process. For us, a unique difficulty posed by the consortium style of the Claremont Colleges was securing approval from each of the 5 colleges’ administrations. Overall, flexibility and adaptation will serve other institutions well when using our experience as a guide to establish their own service.

This article addresses the detailed steps necessary to establish a collegiate EMS program. Our team at the Claremont Colleges worked tirelessly with our Dean of Students, Student Health Services, and the Campus Safety department to bring this idea to fruition, but it would not have been possible without the guidance of established organizations from other institutions. This piece is intended to provide insight into the establishment of collegiate EMS programs and serve as a comprehensive guide of important considerations. Our team at The Claremont Colleges hopes that this guide will facilitate your experience in creating a collegiate EMS program, and that you will use it to further emergency medical knowledge within your own community.

If you have any questions/comments pertaining to the article or would like personalized advice for establishing your collegiate EMS, please contact us at ClaremontCollegesEMS@gmail.com

Authors’ Remark

Of note, 4 of our 7 authors (Ryan Ferdowsian, Emma Finn, Tanvi Shah, and Natalie Tsai) were also inaugural employees of our Campus Safety EMS. We decided to begin writing this manuscript shortly after realizing that the service would be postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As members of the service, one of our primary goals was to improve community health and wellbeing. We found that this project allowed us to indirectly achieve our goal by providing resources other communities could use to similarly improve the health and wellbeing of their members. In conclusion, we urge you to be resilient when faced with unexpected challenges by searching for alternative methods to serve your community and those surrounding.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to The Assistant Vice President of Campus Safety at the Claremont Colleges whose support, advocacy, and mentorship were instrumental in the creation of our service. Furthermore, we would like to recognize our medical director for his dedication to our cause and guidance in the creation of our medical protocols.

References

- Fisher J, Ray A, Savett SC, Milliron ME, Koenig GJ. Collegiate-based emergency medical services (EMS): a survey of EMS systems on college campuses. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006;21(2):91-66. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00003411. PMID: 16770998.

- Struve OA. Design and implementation of a sustainable, university-based, emergency medical response service. Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Projects. 2014;26. https://repository.usfca.edu/dnp/26

- Fraccastoro KA, Moss G, Flosi A, Karani K. Disseminating information to college students in a complex media environment. Business Education Innovation Journal. 2020;12(1):49-53.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A: Professionalism

Appendix B: Longevity Practices

Appendix C: Student Survey Questionnaire

Author & Article Information

Ryan Ferdowsian, BA, NREMT was an employee of the Campus Safety EMS, the Co-President of the Claremont Colleges EMS Club, and received his BA in Medical Economics from Pitzer College. Tanvi Shah, BA, NREMT was an employee of the Campus Safety EMS, was a member of the Claremont Colleges EMS Club, and received her BA in Neuroscience and Humanities: Interdisciplinary Studies in Culture from Scripps College. Emma Finn, NREMT was an employee of the Campus Safety EMS, was the President of the Claremont Colleges EMS Club and received her BA in Science Management from Claremont McKenna College. Aditi Chitre, NREMT is the Co-President of the Claremont Colleges EMS Club and is currently working to obtain her BA in Neuroscience and Philosophy from Claremont McKenna College. Natalie Tsai, NREMT was an employee of the Campus Safety EMS, is the Co-President of the Claremont Colleges EMS Club and is currently working to obtain her BA in Science Management from Scripps College. Max Wragan was a member of the Claremont Colleges EMS Club and is currently working to obtain her degree in Neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania. Ananya Koneti is the Chair of External Programming at the Claremont Colleges EMS Club and is currently working to obtain her BA in Science Management from Claremont McKenna College.

Author Affiliations: From Campus Safety EMS; Claremont Colleges EMS Club; Pitzer College – in Claremont, CA (R.F.). From Campus Safety EMS; Claremont Colleges EMS Club; Scripps College – in Claremont, CA (T.S.). From Campus Safety EMS; Claremont Colleges EMS Club; Claremont McKenna College – in Claremont, CA (E.F.). From Claremont Colleges EMS Club; Claremont McKenna College – in Claremont, CA (A.C., A.K.). From Claremont Colleges EMS Club; Scripps College – in Claremont, CA (N.T.). From Claremont Colleges EMS Club – in Claremont, CA; University of Pennsylvania – in Philadelphia, PA (M.W.).

Address for Correspondence: Ryan Ferdowsian, BA, NREMT | Email: RFerdow@students.pitzer.edu | Phone: 650-704-663

Conflicts of Interest/Funding Sources: By the JCEMS Submission Declaration Form, all authors are required to disclose all potential conflicts of interest and funding sources. All authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest. All authors declared that they did not receive funding to conduct the research and/or writing associated with this work.

Authorship Criteria: By the JCEMS Submission Declaration Form, all authors are required to attest to meeting the four ICMJE.org authorship criteria: (1) Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND (2) Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND (3) Final approval of the version to be published; AND (4) Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Submission History: Received December January 24, 2021; accepted for publication July 2, 2021.

Published Online: October 31, 2021

Published in Print: October 31, 2021 (Volume 4: Issue 2)

Reviewer Information: In accordance with JCEMS editorial policy, Advice and Practice manuscripts are reviewed by the JCEMS Editorial Board and, as needed, independent reviewers. JCEMS thanks the Editorial Board members and independent reviewers who contributed to the review of this work.

Copyright: © 2021 Ferdowsian, Shah, Finn, Chitre, Tsai, Wragan & Koneti. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The full license is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Electronic Link: https://doi.org/10.30542/JCEMS.2021.04.02.02